Learning the Loess Hills

By Elizabeth Koele '16

LAS 410: Ecotones: Exploring Literature, Science, and History

Liz enchants the reader with a personal journey and connection to Iowa’s Loess Hills, the landscape she calls home. I particularly appreciated her focus on time as well as the layered integration of natural history, art work such as George Catlin’s “Grassy Bluffs, Upper Missouri” and her personification of the hills. The power of “Learning from the Loess Hills” encourages readers to understand this fragile treasure and protect these gentle “friends” from human impact and encroaching ecological threats.

-Mary Stark

Ides of March (cut branch fires near Missouri Valley), 1994

Keith Jacobshagen (by permission)

18” x 46”

Driving north along the edge of Western Iowa, the flat land surrounding the Missouri River is the definition of perfect farmland. The soil is full of nutrients and technology allows water from the Mighty Mo to be pumped into huge sprinkler systems. Glancing out my window, I look back at the large hill I had just descended, which stretches into the distance. This long line of raised earth will follow me the rest of the way home. Through those last 90 miles, it will range from looming over the road as I slide down its slopes to change interstates, to retreating to the distant edge of the horizon. Somehow, the hills’ presence seems to grow the further they recede from my point of view. They appear all the more amazing defiantly interrupting the flat farmland, Iowa’s very own mountains standing sentinel throughout time. Before I arrive home, I will climb the hills one last time, reaching the last leg of my journey. For a short time, my way will proceed along their opposite edge. We part ways a short distance from our separate destinations, and I bid the hills adieu, assured they will be able to manage the remaining miles unaccompanied. As promised, we both reach our end, a mere 25 miles apart and although we neither started nor ended our journey together, it was pleasant to have a familiar companion for part of the way.

* * *

As the bus climbed the hill, the excitement among the third graders was uncontainable, and when the vehicle finally bounced to a stop in a plume of gravel dust, we spilled out onto the grass of the recreation area. It was Fieldtrip Day and we were visiting Hillview Recreational Park, one mile west of Hinton, Iowa. The park rangers herded us together and attempted to establish some semblance of order. We started off with a hike through the park’s variety of ecosystems. First, we traipsed around the woods, jumping down steps carved into the hillside and skipping along the dirt and mulch paths with energy only found in elementary students. We stopped to poke at weird plants and were instructed on the different animals and trees residing within the forest. The trees eventually gave way to the park’s reconstructed prairie, opening onto waving grasses and the sound of songbirds. By the end of our trek, it seemed as if we had travelled miles. The class gathered back by the shelter house, and a couple of DNR rangers began speaking about what made this area so special. In basic terms they described the complex processes that had gone into creating the landscape around us. As a 10 year old, I didn’t pay a lot of attention to the information they presented. It was hard to believe that these seemingly normal hills were almost one-of-a-kind and had been built up over thousands of year. Little did I know at the time, the hills that had always been present at the very edge of my childhood were far more impressive and complex than I could comprehend.

George Catlin – Grassy Bluffs, Upper Missouri 4

In 1832, artist George Catlin departed from St. Louis, Missouri, beginning his 2,000 miles journey up the Missouri River.2 Along the way he encountered tall waving prairies, Native American tribes and chiefs, and endless herds of buffalo. Eventually, he arrived at the dramatic bluffs and rolling hills along the banks of the river. Catlin marveled at the tall banks, comparing them to “ramparts, terraces, domes, towers, citadels and castles.”3 He depicted these soaring bluffs in a handful of his paintings, sparking the interest of other artists in the process. Little did George Catlin know the lengthy geological processes that had created the hills and bluffs were as laborious as those necessary to create a painting.

Around 25,000 to 12,500 years ago, large glaciers covering the mid-portion of North America began to recede, signaling the end of the last Ice Age.5 As they departed, their massive weight crushed the rock beneath, pulverizing quartz rock into silt. The powdered minerals were swept up by the melted runoff from the glaciers, running down into larger rivers, particularly what is now known as the Missouri River. The silt’s journey was only half over, as the rivers washed the relatively heavy particles into mud flats along their banks. Over time, these deposits dried out and were swept up by strong western winds, which lifted the powder from the Missouri River valley eastward. The heaviest of the pulverized rock and mineral wasn’t carried far, piling up not far from the banks of the river and forming what is today known as the Iowa Loess Hills.6

Although a fairly common type of soil, loess seems to be a mystery to many. It’s found all over the world, but rarely collects in such large deposits and thus is frequently overlooked. From the German word “for loose or crumbly”, it is defined by geologists as a “gritty, lightweight, porous material composed of tightly packed grains of quartz, feldspar, mica, and other materials.”7 It exists in multiple locations across the United States and around the world, which may at first make the hills seem rather ordinary. Other deposits exist near rivers such as the Danube in Germany.8 However, the Iowa Loess Hills are a “geologic anomaly,” worthy of being studied by school children and scholars alike.9 The hills are the second largest in the world. They are surpassed only by the loess hills of Shaanxi, China, which were created far longer ago and stretch deeper than the Iowa formations- an estimated 2.5 million years old and 300 feet deep.10 In contrast, the Iowa hills average 60 feet, but can be as deep as 150-200.11 These impressive statistics alone set aside the Iowa Loess Hills as a geological wonder.

Straddling the very western edge of Iowa, the Loess Hills stretch slightly over the border of Missouri, up until just past Sioux City, Iowa- a length of around 200 miles. They can spread from 10 to 15 miles wide, and overall cover a landscape of approximately 650,000 acres.13 The hills are covered by an incredibly unique ecosystem. Different from the tallgrass prairies to the east and the Missouri River Valley wetlands to the west, the Loess Hills host a mixed grass prairie, which is a mixture between tallgrass and shortgrass determined by moisture levels.14 Although “less than 2% of the hills themselves remain in native grasses and forbs,” these statistics are still better than many other areas in the state, where under 1% of native landscape remains.15 This mix of grasses becomes increasingly unique through its location in the Iowa Loess Hills. Some of the plants found within the hills are almost 100 miles removed from where they would traditionally be located. The environment hosted in the Loess Hills is capable of hosting mixed grasses and other organisms that usually only thrive in the more arid western sections of the United States.16

Further examining this natural phenomenon, the structure and location of the Iowa Loess Hills help create two very different but coinciding ecosystems. The western side of the hills faces directly into the strong winds that frequently rush across Iowa. The orientation also allows for exposure to the hotter afternoon sun, all cumulating to create the aforementioned arid conditions that mimic more western climates. In contrast, the eastern side of the hills is more gradually inclined and is more sheltered from the wind and sun. Upon these slopes condition are more suitable for forests and the tallgrass prairies that used to spread across the rest of the state.17 In recent decades, the presence of forests has steadily increased when before there was only prairie grass.18 This expansion can likely be linked to the increased human population residing in and around the hills. It is incredible to think that within space of a few miles such a drastic change in ecosystems can occur. This mix of climates is just another reason the Iowa Loess Hills are truly one of a kind.

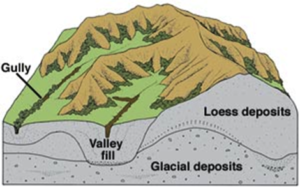

Diagram of the landscape of the Loess Hills 25

Despite being thousands of years old, the Loess Hills are still constantly changing and evolving. Some changes have been occurring naturally but many can be directly attributed to humans. Before the arrival of European settlers, several indigenous groups lived in the Iowa Loess Hills, including the Glenwood, Great Oasis, and Mill Creek peoples.19 They were eventually pushed out by later settlers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The new residents attempted to rework the land to their liking. They “caused erosion directly by digging out roads and cellars in the fragile soil.”20 The groups also worked to stop natural prairie fires. Invasive species of plants, such as leafy spurge and garlic mustard, have lately been introduced to the ecosystem and have begun to choke out the native species. These nonnative plants are especially problematic considering that Iowa’s largest surviving prairies are found in the hills, known as the Broken Kettle Grasslands Preserve. Over the span of a little over one hundred years, human interference has drastically changed the environment and ecosystem of the Loess Hills.21 In addition to the problems posed by human settlement, the Iowa Loess Hills face naturally occurring issues. When they were young, the hills were smooth piles of loosely deposited loess. As they were exposed to weather, the soft soil began to erode into rough, jagged formations. Erosion, both natural and manmade, is undoubtedly the largest threat to the Loess Hills. According to the United States Geological Survey, the Iowa Loess Hills “have one of the highest erosion rates in the U.S., almost 40 tons/acre/year.”22 It’s alarming to realize how quickly the hills are disappearing. As author Robert Grant wrote: “The hills are in a constant process of erosion toward joining the relative flatness of the surrounding countryside.”23 There are several clearly visible examples of the collapse of the Loess Hills. One is the uniquely named catsteps, which are formed when the loess slips and slumps repeatedly down the slope of the hills, creating small shelves of vegetation.24 On the larger scale, large gullies are common in the Loess Hills, large gaps where the natural loess has been carried away by rainfall. They can be miles long, over one hundred feet wide, and as deep as 80 feet.26 Although it seems inevitable that someday the Loess Hills may be no more, for the present it’s important to appreciate the hills while they are still with us.

Through careful study, the Loess Hills emerge as a fascinating paradox. They host two very different ecosystems on their western and eastern slopes, working in harmony. A one-of-a-kind prairie covers the hills, mixing short and tall grasses. The geological composition of the very hills themselves also seems to be a contradiction. Although the loess is soft and unstable, easily eroded by weather, if one were to “cut a Loess Hill vertically…its wall can stand for decades due to the interlocking characteristics of the loess soil particles.”27 The Iowa Loess Hills are an incredibly unique landmark, defining the landscape and ecosystem of Western Iowa for thousands of years. Many are not mindful of exactly how rare the hills and the organisms that live upon them are, and it’s important to spread awareness. The Loess Hills are “dynamic and rapidly evolving,” and the delicate soil that gives the hills their name may someday be completely washed away.28 It would be a tragedy for humans to accelerate the destruction of these irreplaceable hills.

* * *

Sighing as I adjusted the radio, I lamented the fact that my drive back to school had only just begun. It had been less than 20 minutes since I had departed Le Mars, and I have well over three hours left to go. At this point, the landscape was still well-known and loved. I had been driving this route all my life, shuttling back and forth to the amenities and resources offered by Sioux City. Just how many times had I taken this journey? The number was almost impossible to calculate. I glanced out the window, noting exactly where I was: the strange transition between small-town Hinton and the very edges of the city. This area was marked by an increasing number of buildings, and the large substation next to the highway. I passed underneath the massive powerlines that stretched into the distance. Tracing the path of the looming power lines in my mind, I followed them west, where they continued to weave through the gently rolling hills. I could even picture where they crossed another highway I frequented, further into the shadow of the hills. Despite the metal structures’ impressive height, they never quite seemed to dwarf the proud presence of the ancient hills I call friends.

Works Cited

- Cornelia Fleischer Mutel, Mary Swander, and Lynette Pohlman, Land of the Fragile Giants: Landscapes, Environments, and Peoples of the Loess Hills (Iowa City: Published for the Brunnier Art Museum at Iowa State University by the University of Iowa Press, 1994), xvi-xvii.

- Ibid, xv.

- Ibid., xvi.

- “Grassy Bluffs, Upper Missouri,” National Gallery of Art, accessed November 23, 2015.

- “Geology of the Loess Hills, Iowa,” USGS, last modified July 1999, accessed November 16, 2015.

- Robert L. Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic Environmental Ethics: The Ecological Crisis in the Loess Hills of Iowa (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2007), 18.

- “Geology of the Loess Hills, Iowa.”

- Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 20.

- Ibid.,20, 9.

- “Geology of the Loess.”

- Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 19.

- “Unique Features of the Loess Hills,” Loess Hills National Scenic Byway, last modified 2014, accessed November 16, 2015, http://visitloesshills.org/.; “Iowa: The Loess Hills,” The Nature Conservancy, last modified 2015, accessed November 16, 2015.

- Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 16.

- Ibid., 10.

- Ibid., 18.

- Ibid., 20.

- Mutel, Swander, and Pohlman, Land of the Fragile, xxi.

- Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 20.

- Ibid., 21.

- “Iowa: The Loess Hills,” The Nature Conservancy.; Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 23,33.

- “Geology of the Loess.”

- Grant, A Case Study in Thomistic, 19.

- Mutel, Swander, and Pohlman, Land of the Fragile, xxi.

- “Geology of the Loess.”

- Ibid.

- “Unique Features of the Loess,” Loess Hills National Scenic Byway.

- “Geology of the Loess.”

- Mutel, Swander, and Pohlman, Land of the Fragile, xvi-xvii.; “Randy Becker’s Crows over the Catsteps also speaks of humanity’s attempted dominance over the land. While birds dance in the sky over the stepped hills, high-power lines dissect heaven and earth. ”