Carmen: Power Struggle and Exoticism

By Brandon Mennenoh '15

HONR 499: Senior Honors Thesis

Brandon’s anthology selection is an excerpt from his Senior Honor’s Thesis. I chose to nominate Brandon’s writing because his analysis is original and interdisciplinary, and is supported by thorough research. Brandon and I had many long and enjoyable discussions about gender representations in music, and about how music reflects the time and place in which it was composed. Hopefully after reading Brandon’s insightful analysis of Carmen, you will think twice about what today’s music says about who we are.

-Cynthia Doggett

The exotic life of the gypsy as depicted in Carmen reflects the political unrest of nineteenth century France and the power struggles of race, social class, and gender. Bizet’s setting of the plot reflects his political opinions regarding the French government’s actions toward minorities. The musical exoticism written into the role of Carmen, a classic femme fatale, reflects contemporary beliefs regarding sexuality, class, and race. She is an “other” in opposition to the hegemony of the white male Caucasian represented by Don Jose. Bizet’s use of exotic compositional techniques portrays the carefree life of the gypsy and reflects the racial, socioeconomic, and gender attitudes of the time period. Through musical analysis and historical context, I will return to the true voice and message of Carmen—one that would have been understood by audiences at the time of its premiere.

The image of the gypsy figure was very attractive in nineteenth-century France because of the political strife. The French had suffered a civil war in the year 1848 followed by the Franco-Prussian War. This war brought a great defeat to France and placed the country in a humiliating position in world power.1 After the war with Germany, there was an eight-month rise of the communist party known as the Paris Commune. The Commune was a movement to counter the government of Versailles, which was implemented after the overthrow of Napoleon III. In Paris, anti-bourgeois attitudes were rising again and the resulting massacres were leaving thousands of citizens dead in the streets.2 Ambiguity was what made gypsy life so attractive. Gypsies were renegades from a pre-modern culture who did not have to live within the bounds and structures of a modern Western society. A character like Carmen defied the lines of social class and authority in a time when the French government had partial responsibility for the carnage of the Commune.

Carmen and her gypsy community were a threat to society because of the unrestrictive, obscure life that they led. Gypsies, Jews and other ethnic minority groups were considered outsiders and aliens even if they lived on French soil. These ethnic minority groups became a more prevalent force when the bourgeoisie employers extended employment to them due to the revolutions in 1830, 1848, and 1871. While they were functioning members of society, they were considered inferior to the white French population and required to stay in their place. They were feared and labeled a danger because they straddled the line of European and Other, and their communities were seen as an outlet for lechery and corruption.3 They spoke the French language but also remained fluent in their native tongues.4 Don José represents order with the power to destroy, while Carmen represents the people of the commune who defied the law and fell victim to the government in the end.

The life of a gypsy (La vie bohème) portrayed in Carmen was also a personal expression for the composer for two reasons. First, he was not accepted by his wife’s family and was referred to as a “Bohemian and an outsider.”5 Second, as a member of the French military he had experienced the political massacre firsthand and expressed in letters to his mother-in-law his distaste for society: first with Napoleon, then with government under Adolphe Thiers, and lastly, with the bloodshed that was occurring during the Commune.6 In nineteenth century France there was a fascination with the exotic, specifically with the East and the Orient; this will be mentioned in greater detail later in this paper. A figure commonly associated with the exotic was that of the gypsy woman.

21

In Bizet’s opera, Carmen is a free spirit that has to be controlled. The character of Don José reflected the white bourgeoisie attraction to the free, spirited life of the gypsy. Don José’s attraction becomes fatal because of his need to control her. Society gives Don José control over Carmen because he is a white, middle class male. The military occupation of Seville draws the lines of gender, class, and race at the opera’s opening. The white Spanish soldiers are trusted to keep the peace while the women are the laborers. The soldiers stand by and gawk at the women as they leave and enter the cigarette factory. While the factory girls are in an inferior position to the soldiers because of their gender and race, they still serve as a spectacle for the men.7

15

Carmen becomes Don José’s subordinate further after she stabs a white factory laborer who calls her a slut and is placed under Don José’s guard. Audience members may perceive Carmen as dangerous because of this action and the fact that she convinces Don José to disobey orders and help her escape in exchange for sexual favors. Don José surrenders himself sexually and there is a battle of control. Don José interprets the act as a long term commitment and Carmen treats it as repaying a debt and a temporary sexual encounter. Carmen is an untamed spirit who knows not the bounds of subordination; she does not submit to Don José and does not regard the lines of gender, race, and class. Don José fights to regain control and to control Carmen which ultimately leads to him slaying her.8

Exoticism and chromaticism are the most prevalent features of Carmen. A figure commonly associated with the exotic was that of the gypsy woman. During the time of political unrest in France, there was a fascination with the Orient. Musicologist Susan McClary states that “…the ‘Orient’ (first the Middle East, later East Asia, and Africa) seemed to serve merely as a ‘free zone’ for the European imagination.”9 Setting musical works in the orient gave composers the opportunity to criticize their own culture. Don José is an example of how a European man can be drawn into the sensual nature of the orient.10 In exoticist research “the Other” is often used. The definition of “the Other” simply means something or someone outside the norm. This included gypsy and ethnic minority populations that immigrated to France such as: Persian, Jewish, Greek, African, and Spanish communities.11 When Bizet composed this opera, “the East” and “the orient” became personified as a woman. “The East as a whole became ‘feminized …and just as Don José…the audience is lured into Carmen’s world ‘almost without having wished it.”12

18

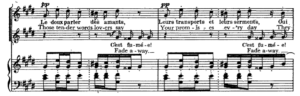

Even though Spain was a part of Western Europe, it was considered an oriental country. The Spanish in France were known as Arabs who were Christian. Artwork from Spain was brought back to France and Spanish literature became extremely popular. The gypsy community became the epitome of Spanish culture because of literary and artistic depictions.13 Carmen’s aria in Act I the Habanera aria (L’amour est un oiseau rebelle) is the most famous exotic work because it is based on a Cuban dance. In the below excerpt from the aria, the melody line descends chromatically giving the song a promiscuous feel, and the lyrics of the aria are enhanced by the sensuality of the piece. The opening lyrics of the aria summarize Carmen’s way of life: “Love’s a bird that will live in freedom…”14 This aria is reprised at the end of the first act before Carmen escapes military custody.

24

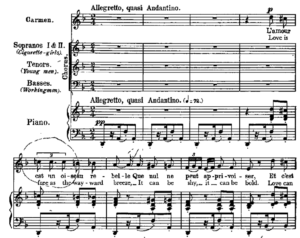

Musicologist John Locke stated in his research that exoticism is not only music that sounds exotic but appears exotic in costuming, scenery, and situations. He highlights that the Card aria from Act III is exotic because while French in its musical construction, it depicts the practice of fortune telling, a distinguishing feature of gypsy life.16 Below is an excerpt from the scene that Mr. Locke makes reference to. The fortune telling scene “conveys ethnic or exotic characterization without ethnic or exotic style…”17 The viewer can see that there is no extreme chromaticism like in the example from Habanera and the scene remains in F major. In this scene, the characters of Carmen, Frasquita, and Mercedes are dealing the cards in order to reveal their fortunes. 18

25

The opening scene as well is oriental because of the Spanish scenery and costuming even though the music at this point has no Spanish traces. Some of the gypsy music in Paris was not authentically Spanish, even though Bizet researched Spanish music. “Gypsies performed their exotic songs and dances for the benefit of popular audiences in Paris and Bizet often frequented their haunts of ill-repute for entertainment.”19

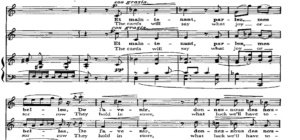

Bizet incorporated chromatic harmonies and melody lines represent promiscuity and sexual desire. In the opening scene, the cigarette smoke from the factory women is represented chromatically. The cigarette smoke also shows the sexual availability of the gypsy women and their sensuousness and unpredictability. This is also a historical reflection because in nineteenth century France, it was not socially acceptable for women to smoke. If a man saw a woman smoking it often meant she was a prostitute. The excerpt below is taken from the chorus of factory women. The chromaticism in the orchestra embodies the rising cigarette smoke and the vocal lines of the women represent their sexual availability.20 Don José is represented diatonically while Carmen is captured with dissonance and chromaticism.22

26

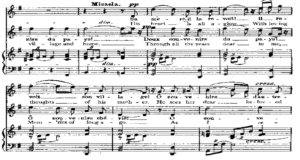

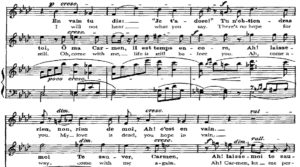

Bizet created the character of Micaela as a direct contrast to Carmen. While Carmen represents a life of free-spirit and no limitations, Michaela exemplifies conventionality and piety. The example below is from Micaela’s aria from Act III. Unlike Carmen, whose arias have a very chromatic, seductive nature, this aria is lyrical and symbolizes purity and chastity. The tonality of Micaela’s aria has a heavenly nature to it. The plagal or “Amen” cadence appears in the accompaniment.23 In this example, the tonality remains in F major and the instrumentation and tessitura give the song an angelic feel opposed to Carmen. Because the roles of Micaela and Carmen are meant to foil one another, Don José’s tonality changes based on who he is singing with. The first excerpt is from the Act I duet between Micaela and Don José, Parle-moi de ma mère. The tonality of the piece remains in the major key with little chromaticism. Any chromaticism that appears is used to highlight the emotion of the news that Don José’s mother is sick and wants to see him before she dies. The final excerpt is taken from the scene leading up to Carmen’s death. In this scene, Don José’s vocal line ascends chromatically. The chromatic ascension shows Don José’s sexual frustration with the fact that Carmen cannot be controlled. Carmen musically portrays gypsy life with its exotic depictions and chromatic elements. The plot line, tonality, and character representation reflect the power struggle and political tension of nineteenth-century France. The opera also highlights the struggle between the dominant male figure and the femme fatale.

- Dallas, Gregor. “An Exercise in Terror? The Paris Commune, 1871.” History Today, February, 1989, 38-44.

- Wrong, George M. “Paris in 1871.” The Lotus Magazine, March 1918: 279-80, 282-88.

- McClary, Susan. Carmen: Georges Bizet. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- McClary, 34.

- Curtiss, Mina, and Georges Bizet. “Unpublished Letters of Bizet.” The Musical Quarterly (Oxford University Press) 36, no. 3 (July 1950): 375-409.

- Curtiss, 1950.

- McClary, 47.

- McClary, 60.

- McClary, 29.

- Spain, Exorcising Exoticism: “Carmen” and the Construction of Oriental. “Jose F. Colmeiro.” Comparative Literature (Duke University Press on behalf of the University of Oregon) 54, no. 4 (Spring 2002): 127-144.

- McClary, 29.

- McClary, 31.

- Colmeiro, 127.

- Bizet, Georges. Carmen. Edited by Nicholas John. London: John Caler (Publishers) Ltd, 1982.

- Bizet, Georges, H. Meilhac, and L. Halevy. Carmen: Opera in Four Acts. Translated by Ruth and Thomas Martin. New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1875.

- Locke, Ralph P. “A Broader View of Musical Extoicsm.” The Journal of Musicology (University of California Press) 24, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 477-521.

- Locke, 510.

- Bizet: Carmen, 264.

Works Cited

Bizet, Georges. Carmen. Edited by Nicholas John. London: John Caler (Publishers) Ltd, 1982.

Bizet, Georges, H. Meilhac, and L. Halevy. Carmen: Opera in Four Acts. Translated by Ruth and Thomas Martin. New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1875.

Colmeiro, Jose F. Spain, Exorcising Exoticism: “Carmen” and the Construction of Oriental. Comparative Literature (Duke University Press on behalf of the University of Oregon) 54, no. 4 Spring 2002): 127-144.

Curtiss, Mina, and Georges Bizet. “Unpublished Letters of Bizet.” The Musical Quarterly (Oxford University Press) 36, no. 3 (July 1950): 375-409.

Dallas, Gregor. “An Exercise in Terror? The Paris Commune, 1871.” History Today, February, 1989, 38-44.

Freeman, John W. The Metropolitan Opera: Stories of the Great Operas. (New York: W.W.

Norton & Company, 1984).

Grey, Thomas. “Opera in the Age of Revolution.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History (The MIT Press) 36, no. 3 (Winter 2006): 555-67.

Locke, Ralph P. “A Broader View of Musical Extoicsm.” The Journal of Musicology (University of California Press) 24, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 477-521.

McClary, Susan. Carmen: Georges Bizet. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Marinov, Ivan. Carmen: Alexandrina Milcheva, Nicola Nikolov, Lilyana Vassileva, Nicola Ghiuselev, and the Sofia National Opera Chorus and Orchestra (Delta Music, Inc, 1995).

Wrong, George M. “Paris in 1871.” The Lotus Magazine, March 1918: 279-80, 282-88.

Bizet’s Carmen. DVD, dir. Francesco Rosi (1984; Culver City, CA: Triumph Films).