Thangka: A Guide to Enlightenment

By Gina LeGrotte '14

LAS 410: Buddhist Traditions of Tibet and the Himalyas

Gina LeGrotte is the quintessential interdisciplinary student. She is a psychology major with a strong background in art. And then she also has a very strong interest in religion. So she brings all that to the table; all her interests are on display in her “reading” of that Tibetan Buddhist thangka that hangs in Central Hall Room 316. Although a devout Christian, she is very open to other religious perspectives. Just talking to her, one can tell that her life is a spiritual journey — one that is still looking, open, and alive to all that she encounters.

-Michael Harris

Whether you belong to the Buddhist tradition or hold any other set of beliefs, a thangka can be a journey to enlightenment for you. My first encounter with the Tibetan Buddhist thangka of Padmasambhava at Central College became my first 30-minute meditative journey of the Buddhist way. While I hold to the Christian faith, I feel drawn to the compassion and humility at the core of Mahayana Buddhism and regard this meditation as a way to further my own Christian faith by cultivating similar core virtues. I documented the experience of my own interpretation of the thangka from my initial reaction to deeper and more profound reflections. As I meditate, it is clear that the more time and focus that I use to steady my mind on the teachings of this thangka, the more it guides me into clarity.

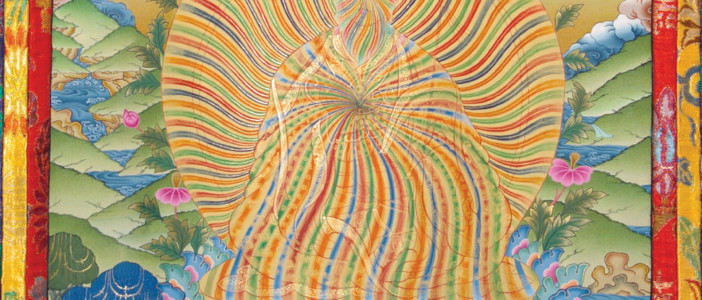

Upon first viewing the thangka, it did not look like there was very much going on. Initially, it seemed obvious that the centerpiece of this thangka is the rainbow figure of Padmasambhava shown sitting atop lotus flowers. He is rising up out of turbulent, mucky waters, symbolizing his origin in the world from which he rose to reach awakening through reason and meditation. The concept that the Buddha has his roots in the world is important to meditate on because it reminds us that we all have the capacity to become a Buddha.

The landscape around him seems to depict the beauty of nature and also the upward path toward nirvana. The tiered or hilly mountains reflect stages of enlightenment or meditation until they culminate in the realm of Buddhahood. This realm of awakening is depicted here as a heavenly place above the world. It is in this realm that we find three celestial bodhisattvas that act as guardians over those who still suffer in the world. A fourth celestial bodhisattva is shown sitting on the earth right next to the turbulent sea. This is fitting because, as David Timmer points out, she is the goddess of salvation from danger and misery. She may have overcome suffering, but she has not separated herself from the world. Her compassions for the suffering of others bids her to stay in the world in order to help others attain enlightenment.

The silk frame serves as a guide into the thangka. The dark blue background of the frame leads us into the Buddha’s heart, which culminates in a dark blue center. Yet, if our gaze is caught by the colors of the lotus flowers in the frame, they also lead our eyes back into the Buddha because the lotuses are made from the same colors as the rainbow Padmasambhava. It is as if the painting is guiding me across the canvas. With this realization, it becomes clear that the thangka is not just a bunch of symbols and hidden meanings; it is a guided journey.

A good piece of art always has the power to move our eyes across its surface in a specific path. I learned of this power while I was attending art school at Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia. Applied to this thangka, I find that, no matter where my gaze starts, my eyes are first drawn to the center of Padmasambhava’s heart. From the heart, I slowly descend to the place from which the Buddha has arisen. I am surprised to find that he comes from such a violent place that it can be rendered as tempestuous waters. Yet, in this unsettling place, I meet Tara who encourages me to start on the path toward awakening that will ultimately cease all my suffering.

From the raging sea, I start to climb up the mountain in an effort to protect myself from this place of suffering and to search for a place of peace and safety. As I slowly climb, I come upon the summit of the mountain and, in a climactic moment, I catch sight of the celestial beings. Yet, as I stand atop the mountain to peer up at these magnificent beings, I realize that I have not yet reached the state of mind that is necessary to remain in this heavenly abode. I am led back down into the heart of the Buddha to reflect on his wisdom and compassion.

With the leading of the eyes, the thangka transforms from a magnificent piece of art to a tool for teaching and meditation. The cyclical journey draws the viewer into a never-ending story that he may meditate on for as long as he needs. The story teaches us that the heart of the Buddha is powerfully compassionate, full of wisdom, and open for contemplation. This heart of compassion extends softly and effortlessly into the world around him. Padmasambhava’s heart radiates into the world, but not like rays of the sun, which are straight, forceful beams of light. This unobtrusive extension of Buddha’s compassionate heart is illustrated using lines that softly undulate outward into the world.

While Padmasambhava is the centerpiece of the thangka, his humility is evident in the subtle lines that delineate his form. The viewer can barely distinguish the outline of Padmasambhava’s figure within the rainbow halo that surrounds him. The artist does not want us to get caught up in the thought that it is Padmasambhava, in bodily form, that is the focus of our meditation. Rather, it is the wisdom and reason in his mind (sprouting from his third eye) and the compassion in his heart that should be at the center of our meditative contemplations.

With all these magnificent qualities, the Buddha seems to be something that is quite unattainable, but the thangka teaches us that we can follow in his ways and achieve the same end. Buddha has risen from the hardship, suffering, desire, and ignorance that we experience every day. Yet, we begin to overcome the pain of this world when we see that Padmasambhava has no body, no self. He is only for the benefit of others and does not expect fame or power to come from his generosity. Padmasambhava reached enlightenment and, in this awakened state, his goal is to extend his wisdom to the world. As we begin to meditate on this, we reflect on a concept of no-self or emptiness.

If we meditate long enough and allow our mind to steady itself on the thangka’s teachings, we start to move through stages of meditation. The celestial bodhissatvas become different sources of meditation for us. We meditate on wisdom, on compassion, and on defending ourselves from demons. When we meditate on wisdom, we want to push away all ignorance and all misconceptions of ourselves so that we can see things for what they truly are. When we meditate on compassion, we want to give all of what we are to the world around us in order to cease the cycle of suffering for all people. When we meditate on defending ourselves from demons, we want to push away slothfulness, apathy, and untamed thoughts. Focusing our mind on these ideas brings us an understanding of them and eventually this understanding brings a change within us. We are able to reach higher and higher stages of meditation and reason as we climb closer and closer to becoming fully enlightened.

My experience with the thangka exceeded my expectations. I left with a sense that I had moved forward without even taking a step. It seemed as if I were taking a journey that I had gone on before, like I was reliving a memory. If nothing else, this viewing encouraged my respect for Buddhism and enhanced my desire to reflect on the concepts that I have yet to understand. This journey through the thangka of Padmasambhava will not be my last voyage into the beauty of Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhist Thangka Tapestry – Central Hall Room 316reflect