The Art of Becoming Ordinary: An Analysis of The Handmaid’s Tale

By Kaity Sharp '14

Literature by Women

For this assignment, students were to write a paper focusing on an important theme in Margaret Atwood’s novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. Kaity is an accomplished writer, and I could have submitted any of the papers she has written for Literature by Women. Her paper on The Handmaid’s Tale stood out for the clarity of her argument and her choice of the theme of how the dystopia of Gilead succeeds in becoming “ordinary.”

-Kim Koza

“‘Ordinary,’ said Aunt Lydia, ‘is what you are used to. This may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time it will. It will become ordinary’” (Atwood 45). In Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the Republic of Gilead initially appears to be anything but ordinary. The United States no longer exists and in its place is a new totalitarian government in which every person is valued (or unvalued) for the specific role they play in society. A Handmaid like Offred, for example, is only valued for her womb because reproduction is her only purpose. Women in general have lost all of their civil rights. In fact, they are not even supposed to have desires. A new language with terms like “Particicution,” “Unwomen,” and “Econowives” has developed. People are hanged publically for being homosexual, belonging to a certain religious group, or disobeying the rules that come with their roles. “Ordinary” isn’t a word that seems to accurately describe the dystopia of Gilead. However, according to Aunt Lydia, “ordinary” is simply “what you are used to.” These words come back to Offred as she is looking at the lifeless bodies hung upon the Wall for the citizens to see. How could something so terrible ever become ordinary? Yet as she looks at the hanging corpses, all Offred feels toward them is “blankness” (Atwood 44). She is already attempting to get used to this new life. Atwood makes the reader believe that a dystopia like Gilead could ultimately succeed in becoming “ordinary” because it is structured so that people will be complacent for a little compensation, it is easier for them to be ignorant of the horror and forget, and future generations will not know any differently.

Gilead stays in control for a number of reasons. As Shirley Neuman writes, “[Atwood’s] Gileadean government maintains its power by means of surveillance, suppression of information, ‘re-education’ centres, and totalitarian violence”(Neuman 1). With its harsh punishments for breaking the rules, Gilead forces its citizens to be complacent by using their fears against them. Small resistances will never work because the government can easily torture and kill these resistors, therefore scaring the others into obedience. Offred eventually learns that she cannot even expect the strongest, like her mother and Moira, to succeed in their individual resistances when she does not have the courage herself to rebel: “And how can I expect [Moira] to go on, with my idea of her courage, live it through, act it out, when I myself do not?” (Atwood 324).

Although Gilead succeeds by forcing its citizens into complacency through violence, perhaps a less evident but even more important way it works is by rewarding those that are complacent with small freedoms. “Humanity is so adaptable,” Offred remembers her mother saying. “Truly amazing, what people can get used to, as long as there are a few compensations” (Atwood 349). This statement pertains to many of the major characters in the novel. If ordinary is simply “what you are used to,” and Offred’s mother’s statement is correct, this means that people will be willing to adapt and consider something ordinary in exchange for “a few compensations.” Perhaps that is why the Aunts, like Aunt Lydia, are willing to take part in the preservation of Gilead, even though this life isn’t easy for them, either (Atwood 74). Maybe that is why Wives like Serena Joy allow their Handmaids to become pregnant by their husbands, despite terribly jealous feelings. They all get a little compensation, a little freedom or power in return. Men were the primary creators of Gilead, but women like the Aunts are equally responsible for keeping the totalitarian government running. As Aunt Lydia occasionally hints, the Aunts are not particularly happy with their jobs in Gilead, yet they contribute to its existence because of the special perks they receive. They are the only class of women allowed to read, and although they are older and infertile, their positions as Aunts prevent them from being shipped off to the dreaded colonies. The Wives’ high statuses also give them this security and more freedoms, which is why they, too, choose to be complacent and put up with the Handmaids. As Offred’s mother suggests, people will “get used to” something out of the ordinary if they get something in return. Gilead works as a whole because its citizens are willing to adapt to their roles in society in exchange for the minor benefits and protections they receive.

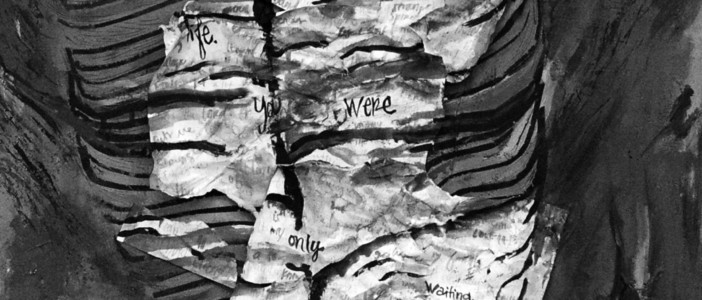

Sarah Shimon, “Untitled,” Acrylic on Masonite, 4’ x 2’

In the beginning of the novel, Offred isn’t ready to adapt to her role in society. Throughout the story she is constantly reflecting on the way things were, as if reminding herself that there was a time when life was different, when it was better. Her life as a Handmaid is especially difficult because she remembers her past and is aware of how drastically everything has changed. Even the Aunts understand this: “You are a transitional generation, said Aunt Lydia. It is the hardest for you. We know the sacrifices you are being expected to make” (Atwood 151). Offred and the other Handmaids know that life could be better for women because they once lived in a time when it was. However, for future generations, life in Gilead will be all that they know. They will not have to adjust like Offred did; therefore, life may be a little more bearable: “For the ones who come after you, it will be easier. They will accept their duties with willing hearts” (Atwood 151). When Aunt Lydia explains this, Offred notices that “She did not say: Because they will have no memory of any other way. She said: Because they won’t want the things they can’t have” (Atwood 151). Offred knows that life in Gilead will become ordinary in the future because people will not remember it any other way, but Aunt Lydia implies that the “wanting” is the main problem with Offred’s generation. Most of them do want what they cannot have—the freedoms of their lives before Gilead. As Offred says later in the novel, “To want is to have a weakness” (Atwood 152). Yet she continues to be weakened by everything she wants. She wants to bicker with her husband Luke, she wants to go to the Laundromat, she wants to laugh with Moira, she wants her daughter back. She wants to believe that she is telling a story, because if she is, then “[she has] control over the ending” (Atwood 52). If it is a story, there will actually be an ending and “real life will come after it” (Atwood 52). But part of her knows that what is happening is real, and she can’t change it. She must simply hold onto her memories of the past and hope for a better future. Offred constantly thinks of Luke and Moira and of her daughter and mother because remembering them reminds her that they did exist and that maybe they still do: “I try to conjure, to raise my own spirits, from wherever they are. I need to remember what they look like. I try to hold them still behind my eyes, their faces, like pictures in an album” (Atwood 250). But as her new life becomes more and more ordinary, her memories of her old life begin to disappear: “But they fade, though I stretch out my arms towards them, they slip away from me, ghosts at daybreak…It’s my fault. I am forgetting too much” (Atwood 250). Even Offred, part of the “transitional generation,” begins to forget. Her ability to remember a life before Gilead is what will make her different from future generations, but even this is slipping away. She must continue to want a new life. “Wanting” could be considered a weakness, but it is also precisely what prevents the horrors of Gilead from becoming ordinary. For as we see toward the end of the novel, once Offred stops wanting her old life, she becomes more complacent with the one she has.

Toward the end of the novel, even Offred, our protagonist, falters and begins to accept her life in Gilead for a little compensation. The more she gains from her situation, the less she wants it to change. After she starts her secret affair with Nick, she feels a connection with another person again and will do anything to keep it. Offred knows that their relationship puts her in an extreme amount of danger, but she is “beyond caring” (Atwood 347). She begins to lose her previous desire to take part in the resistance and is actually comforted when Ofglen stops pressing her for information: “Ofglen is giving up on me. She whispers less, talks more about the weather. I do not feel regret about this. I feel relief” (Atwood 149). In a way, Offred gives up on herself. She has been worn down, and now all it takes is a little compensation to make her give up her fight. Although she is “ashamed” to admit it, she doesn’t want to escape anymore: “The fact is I no longer want to leave, escape, cross the border to freedom. I want to be here, with Nick…” (Atwood 348).

In her article “’Just a Backlash’: Margaret Atwood, Feminism, and The Handmaid’s Tale” Shirley Neuman argues that, “[Offred’s] affair with Nick marks a relapse into willed ignorance” (Neuman 5). This “willed ignorance” is what helped create Gilead in the first place. In pre-Gilead times, Offred and other women chose to ignore the terrible stories of things happening around them because they were not directly involved. This choice to ignore is the “willed ignorance” Neuman suggests. As Offred says, “We lived, as usual, by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it” (Atwood 74). They didn’t want to believe what was going on so they simply “lived in the gaps between the stories”(Atwood 74). It was easier this way. Neuman explains that Offred quickly learns about the importance of paying attention in Gilead, and “…early on in the novel, she is alert to every detail around her.” However in the end, her affair with Nick causes “a relapse into willed ignorance” that leads to her uncertain fate. When Offred stops caring, stops wanting change, and starts ignoring what is happening around her, she is in danger of making her life in Gilead “ordinary.”

At first glance, it does not seem as though the Republic of Gilead could ever be considered ordinary. Many humans are not treated as humans in this dystopia, and its violent methods of control are very extreme. However, Atwood succeeds in making Aunt Lydia’s words about Gilead becoming ordinary ring true. For something to become ordinary, people must get used to it. Future generations of Gilead will already be used to the way it is structured because they will not know any differently. Offred’s generation, however, does know the difference because they have lived in a different type of world. Yet, they choose to get used to their new lives in exchange for a little freedom, power, or other minor compensations. After seeing their hopes dashed time and time again, even characters like Offred decide it is easier to become willfully ignorant of the horror happening and accept life for what it is. Gilead should not be considered ordinary, but Margaret Atwood succeeds in making the reader believe that “ordinary” is exactly what the dystopia of Gilead could become.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986. Print.

Neuman, Shirley. “’Just a Backlash’: Margaret Atwood, Feminism, and The Handmaid’s Tale.” University of Toronto Quarterly 75.3 (summer 2006): 857-68. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Web. 29 Nov. 2010.