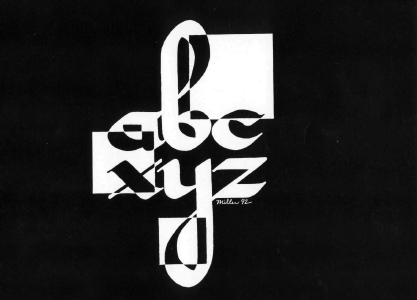

God si Love: Gods in a Middle (An Essay on E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India)

By Dorina Miller '92

Readings in Christianity and Eastern Religions

Writing Objective: Write an essay on E.M. Foster’s novel, Passage to India, in which you address some dimension of the interreligious and cross-cultural relationships among the novel’s western (Christian and/ or non-christian), Muslim, and Hindu characters. Focus on the characters’ (and, perhaps, the narrator’s) world-view and value systems. Seek to employ, whenever relevant, your reading on Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism in Huston Smith. The World’s Religions, John Hinnells, ed., Handbook of Living Religions, and whatever other works on comparative religion you have studied.

The characters of Mrs. Moore and Professor Godbole both express their relationship to ultimate reality in devotional terms, or through bhakti yoga, in E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India. Yet by the end of the book Mrs. Moore realizes the limitations of her idea of God, and it can be seen that Godbole had realized the limitations of Krishna all along—limitations which point to a more overarching experience of ultimate reality, or to the undifferentiated Brahman. This interplay of the dualism of the gods and the non-dualism of Brahman also parallels the images of mud and sky, diversity and stability, echoes and silence, and maya and reality.

Although these concepts and images are not exclusive to either Hinduism or India, A Passage to India portrays the Hindu context of India as more conducive to a realization of Brahman than Western countries such as England. Forster’s first description of the area around Chandrapore, India, in the book is of a land of “mud, the inhabitants of mud moving”— ordinary, changing, yet persisting (4). Here mud is a multifarious image of diversity as mud is an amalgamation of sedimentary elements, but mud is also an image of stability as it is base matter from the earth. The people of India who are closest to the mud have a flense of holiness about them, for they are simple beings who live without as many complex distinctions between themselves, others, and the functionings of the world. Examples include the punkah wallah at Dr. Aziz’s trial who was detached from external events (241), the servant gathering water chestnuts at Mr. Fielcling’s house who comes out of the tank (out of the mud) because he understands the song of Professor Godbole (84), and the villagers at the ceremony of the birth of Krishna who “were the toiling ryot (cultivators of the soil/mud]), who some called the real India” (3 1B).

This “muddy” atmosphere of India leads Mrs. Moore into a gradual realization of the unity behind the diversity of finite being, a unity which she had not felt in England. After returning to the “English” club after her “Indian” encounter with Aziz in the mosque, Mrs. Moore recognizes the differences in the environments:

She watched the moon, whose radiance stained with primrose the purple of the surrounding sky. In England the moon had seemed dead and alien; here she was caught in the shawl of night together with earth and all the other stars. A sudden sense of unity, of kinship with the heavenly bodies, passed into the old woman and out, like water through a tank, leaving a strange freshness behind. She did not dislike Cousin Kate or the National Anthem, but their note had died . . .(28).

Shortly thereafter Mrs. Moore once again recognizes the unity of attributes despite diversity when she identifies the Ganges as both a terrible and a wonderful river (31).

The Indian atmosphere seems to place Mrs. Moore’s Christian beliefs into a muddle, which disturbs the old woman. The first instance of Mrs. Moore’s realization that God is limited carl be seen after her discussion with Ronny about their Christian duty to love their neighbors (53). Following this seemingly unpersuasive conversation, Mrs. Moore contemplates her changing attitudes about God:

Mrs. Moore felt that she had made a mistake in mentioning God, but she found him increasingly difficult to avoid as she grew older, and he had been constantly in her thoughts since she entered India, though oddly enough he satisfied her less. She must needs pronounce his name frequently, as the greatest she knew, yet she had never found it less efficacious. Outside the arch there seemed always an arch, beyond the remotest echo a silence (54).

Here Mrs. Moore is finding God difficult a part of her perception of the muddled diversity of India. Just as the mud is both primary matter and the exemplar of diversity for India, Mrs. Moore’s god had been at the base of her experiences as a Christian, but she was beginning to realize that he is only a portion of her muddled experience of India. God was “the greatest name she knew,” but she was starting to feel that that name and her experiences connected with the name of God were not complete when placed in a larger experiential context.

According to Huston Smith, Mrs. Moore’s changing attitudes about God are a part of her complete maturation: “If we could mature completely we would see that lifespan in a larger setting, one that is, actually, unending” (25). When one is able to see one’s life in relation to the eternal Brahman, as Mrs Moore was gradually beginning to see, one also realizes that finiteness and diversity are relatively less “real,” or that the things of our perception are maya or illusion. Thus her God is seen to be limited, for even though his name was the greatest she knew, it was not. the greatest reality of all—the reality which does not have names or distinctions such as “God” or “Krishna.” Outside of the arch of Christianity there is more, and beyond the name of God there is a silence, for names and words do not apply to non-dualistic reality. “People are forever trying to lay hold of reality with words, only in the end to find mystery rebuking their speech and their syllables swallowed by silence” (Smith 60)

As Mrs. Moore’s ideas about God beoome more muddled she becomes more distressed. At Mr. Fielding’s tea party the guests discuss the fact that “India’s a muddle,” with distinctions between “mystery” and “muddle” drawn by the old woman but refuted by Mr. Fielding.

“I do so hate mysteries,” Adela announced.

‘We English do.” (Mr. Fielding)

“I dislike them not because I’m English, but from my own personal point of view,'” she corrected

“I like mysteries but I rather dislike muddles said Mrs Moore.

“A mystery is a muddle.”

“Oh, do you think so, Mr. Fielding?”

“A mystery is only a high—sounding term for a muddle. No advantage in stirring it up, in either case. Aziz and I know well that India’s in a muddle.

“India’s—Oh, what an alarming ideal” (Mrs. Moore) (73).

Mrs. Moore’s affinity for mysteries is seen in her belief in God and in ghosts (e.g.. P.104), while Adela Quested and .Mr. Fielding profess that they do not believe in either supernatural phenomenon (as is seen in their conversation following the trial – 268). But here Fielding identifies these supernatural mysteries as a part of the muddle of India—part of the diversity which is maya. This alarms Mrs. Moore, for she is once again reminded of the limitations of her god.

While Mrs. Moore has been receiving gradual glimpses of the reality of Brahman, she does not come to a full-blown om experience until she travels to the Marabar Caves. Forster’s description of the land around the caves foreshadows the experience to come, and he once again uses the image of mud to describe the Marabar Hills and the geographical development of India:

The mountains rose, their debris [mudl silted up the ocean, the gods took their seats on them and contrived the river, and the India we call immemorial came into being. But India is really far older. They [the Himalayas! are older than anything in the world (135).

There is something unspeakable in these outposts [the hills]… To call them “uncanny” suggests ghosts, and they are older than all spirit Hinduism has scratched and plastered a few rocks, but the shrines are unfrequented, as if pilgrims, who generally seek the extraordinary, had here found too much of it … [E]ven Buddha, who must have passed this way down to the Bo Tree of Gya, shunned a renunciation more complete than his own … (136)

Nothing, nothing attaches to them (the caves], and their reputation—for they have one—does not depend upon human speech. It is as if the surrounding plain or the passing birds have taken upon themselves to exclaim “extraordinary,” and the world has taken root in the air, and been inhaled by mankind (137).

As the elephant moved towards the hills . . a new quality occurred, a spiritual silence which invaded more senses than the ear. Life went on as usual, but had no consequences, that is to say, sounds did not echo or thoughts develop. Everything seemed cut off at its root, and therefore infected with illusion (154 – 155).

These passages point out, that the experience of the caves is beyond religion, as it is older than the Hindu gods and more complete than the enlightenment of Buddhism, and thus beyond all words and ideas (“spiritual silence”).

Mrs. Moore’s om experience at the Marabar caves is also beyond words and ideas, but likewise it contains all words and ideas. The holy syllable of om (experienced by Mrs. Moore as “boum”) “is said to stand for all sounds and thus for the entire universe” (Hopkins 72). All sounds unite within the “bourn,” pointing to the reality which contains all of the diversity yet transcends the sound itself (“beyond the remotest echo a silence” – 54). This “bourn” is the muddle of maya which points, to the unity of undifferentiated Brahman. Forster describes the echo as

entirely devoid of distinction. Whatever is said the same monotonous noise replies, and quivers up and down the walls until it is absorbed into the roof…. Hope, politeness, the blowing of a nose, the squeak of a boot, all produce “bourn” (163).

The effect of this om experience on Mrs. Moore is a realization of the maya of this muddled world—that the ideas of the self, others, God, and all things are limited in relation to the reality of Brahman. Her identification with the “bigger picture” of ultimate reality produces what seems to be an indifference to, or a detachment from, finite things, including religion.

[The] echo began in some indescribable way to undermine her hold on life. Coming at a moment when she chanced to be fatigued, it had managed to murmur, “Pathos, piety, courage—they exist but are identical, and so is filth. Everything exists, nothing has value.”…

… But suddenly at the edge of her mind, Religion appeared, poor little talkative Christianity, and she knew that all its divine words from “Let there be Light” to “It is finished” only amounted to “bourn” (165-166).

With this experience Mrs. Moore moves beyond her duty to the finite world (her dharma) in order to align her life with Brahman and be a renunciant, or sannyasin. When asked to explain the echo of the caves to Adela, Mrs. Moore replies

“If you don’t know, you don’t know, I can’t tell you. “

“I think you’re rather unkind not to say.” [Adela]

Say, say, say,” said the old lady bitterly. “As if anything can be said! I have spent my life in saying or in listening to sayings; I have listened too much. It is time I was left In peace” (222).

…”Oh, why is everything still my duty? When shall I be free from your fuss? Was he In the cave and were you in the cave and on and on … and Unto us a Son is born, unto us a Child is given … and am I good and is he bad and are we saved? … and ending everything the echo” (228).

The character of Mrs. Moore is closely related to the character of Professor Godbole. a Hindu of the brahmin caste who teaches at Mr. Fielding’s school. While Mrs. Moore came to a gradual realization of Brahman which was beyond her concept of the Christian God, Godbole seems to have this realization throughout the novel but nevertheless he continues to practice bhakti yoga as he worships the Hindu god Krishna. Godbole’s practice of a bhakti which points to the Brahman that both encompasses and goes beyond Krishna is best exemplified in his calling Krishna to “come, come, come, come,” yet being content that he does not come. When Mrs. Moore is still looking for her god to satisfy her, she is disturbed by the thought that he does not come, but later realizes that Godbole speaks the truth She had been calling God more and more during her stay in India, but realized that he does not come because he is a part of the muddle of maya. All divisions are a part of one’s lord, whether he is Krishna or God, just as mud is composed of many parts and the echo encompasses all sounds. But gods, mud, and the echo only point to Brahman; they are not Brahman itself. One can relate to ultimate reality through one’s god, insofar as one is able, and is attracted to her or his god and compelled to repeat, “come, come, come, come,” but he does not come (198). “God [Brahman] stands above the struggle, aloof from the finite in every respect” (Smith 62).

When the character of Mrs.. Moore dies, more emphasis is placed upon her parallel character of Professor Godbole in the third section of A Passage to India Here it is shown how many Hindu practices point to the fundamental om experience already descr¬ibed. Images of mud and muddles return, and Krishna seems to be lost in them both.

The scene of the third section is the celebration of the birth of Krishna in the Hindu village of Mau, where Aziz and Godbole now both live. The entire celebration is one big muddle, but one which proves to be great fun and seems to hold a lot of meaning for the devotees of Krishna. The muddle with an overarching unity can be seen when the villagers gather around the altar to Krishna. They “resemble one another” because of their radiant expressions and then “revert to Individual clods” when the radiance dies away. Similarly, the music “from so many sources … melted into a single mass” (318). The merriment of the celebration shows the world as maya and also Ida, or “the play of the Divine In Its Cosmic Dance—untiring, unending, resistless, yet ultimately beneficent with a grace born of infinite vitality” (Smith 72).

The image of Krishna seems to be lost in the festivities:

[T]his approaching triumph of India was a muddle (as we call it), a frustration of reason and form. Where was the God Himself, in whose honor the congregation had gathered? Indistinguishable in the Jumble of His own altar, huddled out of sight amid images of inferior descent… (319). No definite image survived; at the Birth it was questionable whether a silver doll or a mud village, or a silk napkin, or an Intangible spirit, or a pious resolution, had been born. Perhaps all these things! Perhaps none! (325-326).

One of the many Jumbled images is a sign (“composed in English to Indicate His universality”) which reads, “God si Love.” Forster then asks, “Is this the first message of India?” (320). Considering the themes of mud and muddles throughout the book, a possible conclusion is that this is another way of saying that God (or all gods) are a part of the muddle, or are maya, in comparison to the reality of Brahman. But the gods are vehicles to the experience of ultimate reality—bhakti can shift one’s attention away from the finite self toward unified, infinite reality. Both the Christian god and Hindu gods of bhakti (as well as gods of other religions) are such vehicles, and each can be seen as “God is Love,” but neither is Brahman itself, for all gods neglect to come. The celebration of the birth of Krishna involves “throwing away” the image of God, much as Mrs. Moore did on her passage through India. The villagers assembled by the river,

preparing to throw Cod away, God Himself (not that God can be thrown) into the storm. Thus was He thrown year after year, and were others thrown—images of Ganpatl, baskets of ten-day corn, tiny tazias afterMohurram-scapegoats, husks, emblems of passage a passage not easy, not now, not here, not to be apprehended except when it is unattainable: the God to be thrown was an emblem of that (353)

The last muddle of A Passage to India Involves everything falling into the mud—Krishna, a Hindu, a Muslim, an atheist, and some Christians. “That was the climax, as readily as India admits of one” (354) And the last image of Godbole Is of him smearing this holy mud on his forehead—mud which contains the diversity and the unity of India.

Works Cited

Forster, E.M. A Passage to India. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1924.

Hopkins, Thomas J. The Hindu Religious Tradition.

Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1971.

Smith, Huston. The World’s Religions. San Francisco: Harper, 1991.