Fission or Fusion? The Decision that Changed the World

By Brady Shutt '93

American Foreign Policy

Writing Objective: Write a research paper on an aspect of American foreign policy of your choice.

On January 31, 1950, President Harry S. Truman issued a public statement articulating that he had “…directed the Atomic Energy Commission to continue its work on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen or superbomb.” (a2Public Papers of the President of the United Statesal, p. 138) This excerpt represents the culminations of months of struggle among agencies and individuals in the Truman Administration. The decision to proceed with feasibility studies on the hydrogen bomb escalated an already growing dependence on force-based diplomacy.

The essay will also reveal that many of Truman’s advisors were opposed to the implementation of feasibility studies. A detailed analysis concerning reasons Truman decided in favor of such a program is included. The relative weight of political, technological, and economic considerations will be discussed as they relate to the process of policymaking in the Truman administration. The president’s managerial style will be analyzed, both from Truman’s perspective and from the view of his advisors. This will provide adequate focus on the complex considerations that President Truman and his advisors faced in late 1949.

For the majority of my research I relied on primary sources. Included in this were Truman, George Kennan, David Lilienthal, and Dean Acheson’s memoirs. In this respect I was able to obtain an unbiased view of the key players in the process. In this information, I looked for inner-circle interpretations of the roles of agencies and individuals. This method also provided me direct insight into the decision making process of each individual. By then using this in a part-to-whole method, I was able to clarify the aggregate process.

As stated above, primary sources were used when possible. However, the most detailed work on the process surrounding the decision to develop a hydrogen bomb was Jonathan B. Stein’s From H-Bombs to Star Wars: The Politics of Strategic Decision Making, 1984. This provided a detailed description of the chronological events leading up to January 31. Discussion of committee members and tasks was abundant in the text. This source also provided domestic political insights encountered during the process. These insights were then applied to the key themes of the paper. Stein provided a broad and encompassing base of fundamental knowledge laden with key details. With this detailed background knowledge, research of specific actors in the process was more applicable to the broader scope of decision making.

Of the primary sources, President Truman’s seemed most useful. The obvious reason is that, as president, he was responsible for the dcision to go ahead with the superbomb study. His compilation of personal notes, entitledMemoirs: Volume Tu-o, Years of Hope and Trial (1956), was used to develop a better understanding of his reasons to proceed. More importantly, it uncovered possible contradictions in Truman’s reasoning (included in these are his belief that the public desired more destructive weapons, and his perception of his management style). This source helped decipher domestic political pressures facing the president.

Harry Truman’s public statements, compiled in Public Papers of the President (1950), provided accurate historical data concerning the decision making process in relation to the American public. The significance of domestic political pressures in this essay was enhanced by using this source as a tool to reveiw other works and their validity concerning Truman’s public policy. Because the source contained all of his public statements, it entailed an excess of searching for minimal relevant information. However, the information used was an important means toward the formulation of the thesis of the paper; the significance of domestic political pressures in the process of decision making.

Three other sources were instrumental in my research. These sources were the personal notes and essays of George Kennan, Dean Acheson, David Lilienthal. Each of these men was influential in the policy formulation process. Despite the similarity in format, each of these sources represented a different perspective, in terms of governmental position and area of expertise of the individuals. Kennan’s Nuclear Delusion (1983) was used to gain insight into Soviet intentions and American misperceptions of these intentions. Present At The Creation (1958), a commentary on his years in the State Department by Dean Acheson, helped further understand the State Department’s role in the process. His opinions of other players were useful in defining the “roles” and influence of the various individuals and agencies. David Lilienthal, who served on the special committee of the NSC, articulated several domestic considerations (e.g. Congressional pressure) in relation to technological achievements of the period. Each source fulfilled my research focus of using primary sources and then piecing together the big picture from these sources.

Before examining the domestic conditions surrounding the superbomb decision, it is necessary to discuss the reasons for the sudden emphasis on new, more powerful weapons of mass destruction. In 1946, Bernard Baruch, the United States representative to the U.N. Atomic Energy Commission, proposed the creation of an International Atomic Development Authority. This authority would have considerable international power over all phases of atomic development and use. The Baruch Plan was not implemented due to lack of support from the Soviet Union. (Public Papers of the President of the United States, Pp. 152-53) It must be noted that at this time the only country to have atomic energy capabilities was the United States. Thus, the implication was that the U.S. would, because of leadership in the atomic energy field, be the authority discussed in Baruch’s plan. With this in mind, it is obvious why, given post-WWII tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union, the Soviets voted against the proposal. This suggests that the United States’ major attempt at atomic control before 1949 was slanted and unacceptable in the eyes of the Soviets.

Increased tensions between the Soviets and Americans highlighted the years between 1946 and 1949. The tensions surrounded Soviet intentions in Europe. The Marshall Plan, formation of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the Berlin crisis represent these tensions. The emergence of a bi-polar international system with ideologically opposed poles was evident. The Soviets successful test of the atomic bomb in 1949 altered the course of American policy. Before this, President Truman stated that he was “…firmly committed to the proposition that, as long as international agreement for the control of atomic energy could not be reached, our country had to be ahead of any possible competitors.” (Truman, Memoirs, p. 306) The official Soviet position on the matter was articulated by U.N. representative Vishinsky in November 1949. Vishinsky stated that, “We in the Soviet Union are utilizing atomic energy, but not in order to stockpile atomic bombs.” Vishinsky further stated that, if necesary, the Soviets would have the means and prerogative to stockpile the weapons. (Kennan, Nuclear Delusion, p. 5)

This event, plus the fall of China to communism, marked a turning point for American objectives concerning atomic energy development. Pressure was now placed on President Truman to halt what most thought was the Soviet spread of communism as part of their plot to gain world domination. This essay will now direct focus to the debate surrounding the American repsonse to the events detailed above.

Verifiable knowledge of the successful Soviet atomic explosion led President Truman to privately instruct various agencies and departments to study the feasibility of increased nuclear weapons capability in the form of a hydrogen bomb. Following Truman’s public statement of the Soviets’ test, Lewis Strauss, commissioner of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE), stated in this “Memorandum to the Commissioners” that, “It seems to me that the time has now come for a quantum jump in our planning-that is to say that we should now make an intensive effort to get ahead with the super.” (Stein, From H-Bombs to Star Wars: The Politics of Strategic Decision Making, p. 16) The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) then asked its scientific advisory group, the General Advisory Committee (GAC), to determine the feasibility of such a weapon.

The GAC was unanimously opposed to implementation of a hydrogen bomb program. Two major reasons for this opposition were; 1) the use of limited resources for superbomb exploration and experimentation may detract from current nuclear programs. The fear was that the diversion of resources into a program whose feasibility was unknown would slow our fission (atomic) program to a standstill. 2) The chances of success in the field of the hydrogen bomb (based on the principle of fusion) were unknown. Unknowns, including time, money, and the technological possibility, led the GAC to oppose the idea. There was also the emergence of a moral opposition in the group. The fear that escalation by the U.S. would lead to an international escalation that may eventually result in the destruction of mankind. Thus, fear of an arms race is evident even at this early stage. (Acheson, Present At The Creation, p. 346)

A major underlying theme is evident from the GAC’s unanimous opposition on the ground of feasibility uncertainty. As the scientific advisory body of the Atomic Energy Commission, the commission’s purpose was to articulate the technological possibilities and considerations of the superbomb. That the GAC was uncertain about the feasibility of the program shows that further decisions concerning whether or not the U.S. should proceed would be made in an atmosphere of technological uncertainty. The relative importance of scientific considerations in the decision-making process was small.

Prominent individuals were also against the principle of the superbomb program. George Kennan, one of the foremost experts on the Soviet Union and a member of the Policy Planning Staff at this time, thought the U.S. needed to re-evaluate their atomic policy. Were the weapons vital to our national defense, and as such to be used “immediately and unhesitatingly” in a military conflict with the Soviet Union? Or, were they to be used as a deterrent to the use of such weapons by other countries? The difference between these is the principle of “first strike” that is inherent in the first posture. (Kennan, p. xvi)

Kennan warned that, without a declaration against the principle of first strike, our defense policy would become clouded and out of focus as a tool for foreign policy. Kennan’s concern is that America’s foreign policy would be increasingly based on force and not diplomacy. The further development of weapons of mass destruction would limit the flexibility that traditional diplomacy allows. Kennan understood the importance of nuclear weapons in America’s defense policy. Yet, he felt that these weapons should be under the inspection and guidance of an international agency. This positon was relayed to the State Department in the form of a paper to Secretary of State Acheson in January 1950. (Acheson, Present At The Creation, p. 347)

David Lilienthal, chairman of the AEC, was another opponent of the super program. Lilienthal argued that we needed to re-evaluate our foreign policy objectives. On October 30, 1949, he commented on the implications of the super, “At present…this would not further the common defense, and it might harm us, by making the prospects of the other course-toward peace-even less good than they now are.” (The journals of David Lilienthal, p. 582) Lilienthal felt that the policy review needed to be completed before development of the superbomb was initiated. Further, he felt that American renunciation of instigation of a hydrogen bomb program could serve as a call for attempts at international control. He contended that going ahead with the hydrogn bomb would only reinforce the perception that war with the Soviet Union was inevitable and that the U.S. would be willing to use weapons of mass destruction in the confrontation.

The Atomic Energy Committee was split on the issue. The majority of the commissioners, led by Lilienthal, were against the program. Along with Lilienthal, Sumner Pike and Robert Bacher were hesitant and wanted a full review of policy before instigating the super program. This hesitancy was not felt by Gordon Dean or Lewis Strauss, who were also on the committee. Both were advocates of feasibility studies, and eventual integration of the hydrogen bomb into our defense policy. The AEC postponed recommendation until the GAC report was received. The GAC’s recommendation against the super was not, however, followed by the AEC. In fact, opposition from scientists, career diplomats, and advisory committees was not enough to stop the superbomb program. What reason(s), then, was responsible for Truman’s announcement on January 31, 1950? Thus far, attention has been focused on the separate agencies and individuals in the decision making process. It is evident that the Soviet explosion of the atomic bomb caused great division within the inner circle concerning American response. Attention should now be focused on Truman’s management style and how the decision to go ahead with feasibility studies was reached in the face of widespread opposition to such action. In so doing, focus will be on Truman’s reliance on the State Department, specifically Secretary Acheson, domestic pressures, and Congressional pressure stemming from Senator Edwin Johnson and Senator Brien McMahon.

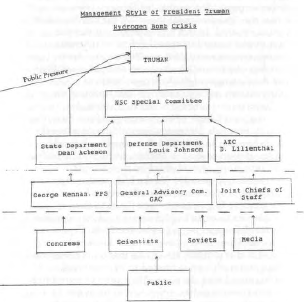

President Truman described his management style in this manner, “I wanted to hear all sides when there was disagreement…I do not believe that the President is well served if he depends upon the agreed recommendations of just a few people around him.” (Truman, Memoirs, p. 305.) In fact, Truman did meet with individual AEC commissioners, scientists, and military experts. Given the disapproval of most of these individuals, one must wonder on what grounds he formulated his final decision. Alexander George, in his book Presidential Decision Making in Foreign Policy: The Effective Use of Information and Advice (1980), describes Truman as playing the role of “chairman of the board, hearing sundry expert opinions on each aspect of the problem, then making a synthesis of them and announcing the decision.” (George, p. 149) George further contends that Truman did not allow political considerations to permeate his decision making (as evidenced by his firing of McArthur during the Korean War). The remainder of this essay will attempt to show that, in the case of the controversy surrounding the hydrogen bomb, domestic political factors dictated Truman’s decision making.

In fairness to President Turman, it must be noted that he did create a Special Committee of the National Security Council. This consisted of the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, and the Chairman of the AEC; Dean Acheson, Louis Johnson, and David Lilienthal respectively. The function of each individual was to use their respective departments and staff to analyze technological, military, and political aspects of the situation. These would be brought together as a joint committee recommendation concerning U.S. action, or inaction, in the field of hydrogen weapons. (Truman, Memoirs, p. 309) Truman also publicly stated, concerning the possibility of releasing public information on the superbomb, “…I make that decision and nobody else.” (Pulbic Papers, p. 134) This shows that, although Truman processed information from multiple sources, he ultimately made the decision based on his synthesis of the situation. What, then, did Truman base his decision to go ahead with hydrogen bomb on?

One factor was the effect the fall of China to communism had on Truman’s image among the American people. Given the anti-communist sentiment in America at this time Truman needed to respond decisively in the latest “threat” to the American people, the Soviets’ atomic explosion in 1949. The American people felt that American nuclear domination was security against Soviet attack. When the Soviets exploded the atomic bomb, this perceived security produced by our atomic arsenal diminished. Public opinion polls in August 1949 show-that 45 percent of the people polled thought that Soviet possession of the atomic bomb made war with the Soviets more likely (only 28 percent thought it less likely). Also, 70 percent were opposed to a formal declaration that the U.S. would not use the atomic bomb as a first strike weapon. (Bernstein, Politics and Policies of the Truman Administration, Pp. 213 6k 214) With these in mind, it may be contended that Truman felt pressure to repsond with a stepped up armament, including a hydrogen bomb.

November 1, 1949, marks the dawning of a new wave of domestic political pressure. It was on this day that Senator Edwin Johnson of Colorado suggested, in a televised statement, that progress was being made on a hydrogen bomb. (Stein, p. 33) It must be noted that, in fact, Johnson was wrong. As of November 1, no progress on the bomb had been made. The importance of his statement lies not in the validity, but rather in the public repercussions. On January 17, The New York Times ran an article, known as the “Reston story,” which probed the possibility of a hydrogen bomb. (Stein, p. 33) Reporters now began to question President Truman during his press conferences at the White House. Truman denied the validity of Johnson’s statement on January 19, when he was specifically asked if he could provide “anything authoritative” to the American people. (Public Papers, p. 34) The increased speculation in the press signifies growing pressure on Truman to respond, with more than “no comment,” to the possibility of a hydrogen bomb program. (Public Papers, p. 18)

Another source of Congressional pressure stemmed from Senator Brien McMahon. McMahon argued that to delay implementation of the hydrogen program would place “a ceiling upon our military advancement.” (Stein, p. 27) Lilienthal described McMahon as one consumed with the belief that the Soviets were set on world domination. Development of the atomic bomb by that country was a positive step in that direction. McMahon contended our only defense was more nuclear firepower. (Journals of David Lilienthal, p. 595) McMahon represents a common American attitude at this time. Most people consumed anti-communist propaganda following WWII. Security, for most, rested on our ability to defend against communism. This placed extra pressure on Truman, being an elected official, to make a decision on the issue of the hydrogen bomb.

It is evident that Truman received mixed recommendations from agencies and individuals. The scientific world, as represented by the GAC, seemed to be against the hydrogen bomb proposal. Other individuals, such as George Kennan, were opposed to the development. Truman was facing increasing pressure from Congress, specifically Senators Johnson and McMahon, the media, and the American people. As a result, Truman turned to the NSC Special Committee as his primary source of information and advise. This suggests that Truman narrowed his attention to a specific body, comprised of three independent departments. In this sense Truman; 1) processed initial information from a very broad base of agencies and individuals, 2) realized that growing political pressure was forcing a decision, and therefore 3) appointed three individuals, as representatives of their departments, to synthesize the existing information into a group recommendation. The three individuals, and their departments, will now be discussed. Following this, the final recommendation, which resulted in Truman’s public statement on January 31, will be analyzed.

Defense Secretary Louis Johnson was a strong advocate of going ahead with the program. He felt that the superbomb would serve as a greater deterrent and would provide better protection against the Soviets. Johnson argued that the “psychological value” of the bomb made it necessary to proceed. In this regard he argued that the American public wanted increased defensive measures. Johnson was against waiting for a re-evaluation of our foreign policy objectives. He cited cost and the possibility of Soviet development of the hydrogen bomb as compelling reasons to begin research. Johnson, and the Defense Department, adhered to the four principles advanced in a Joint Chiefs of Staff memorandum. First, the super would serve as a deterrent. Second, the super would allow flexibility in planning. Third, a superbomb would better utilize resources used in nuclear production. Finally, the Soviet intentions, as evidenced by their atomic capability, made it imperative for the U.S. to develop better means of protection, mainly a hydrogen bomb. In short, the Defense Department urged Truman to take immediate action to begin implementation of the hydrogen bomb in our defense strategy. (Stein, Pp. 21 6k 27)

NSC Special Committee commissioner Lilienthal disagreed with this posture. He argued that a full review of our foreign policy objectives needed to be completed before going ahead with the super. He urged the committee to consider a recommendation that would focus on; 1) expansion of the current atomic program, 2) increased attempts at international control, and 3) immediate, and complete, re-evaluation of our foreign policy objectives. (journals of David Lilienthal, p. 588) His main objection was that simultaneous review of objectives and implementation of the super would slant the foreign policy study. He contended that once we went ahead with increased production of weapons of mass destruction, we could never go back. He also contended that going ahead would merely mask weaknesses in our current defense program and give the American people a false sense of security. For these reasons, Lilienthal advocated completion of a total review of American policy objectives before deciding on the hydrogen bomb matter, (journals of David Lilienthal, p. 628)

Secretary of State Acheson agreed with Lilienthhal’s assessment that our policy needed to be reviewed. However, he thought that doing so before any progress on the hydorgen bomb was made was not politically feasible. Acheson recognized the merit of traditional diplomacy and international control and its value abroad. He also recognized that this had little value in Washington, D.C.: “What he [President Truman] needed was communicable wisdom, not mere conclusions, however soundly based in experience or intuition.” (Acheson, Present At The Creation, p. 347) It must be noted that Acheson and Truman were close friends, and that Truman had backed Acheson on several occasions, despite political pressure to remove him from his position in the State Department. Another possible consideration in Acheson’s recommendation is his shaky political status in 1949. Acheson had been accused of having an underlying support for Algier Hiss. A hard line stance against the Soviets certainly did not hurt Acheson. (Stein, p. 30) Whatever the reason, Acheson advocated simultaneous action regarding the hydrogen bomb and the review of our policy objectives.

On January 31, 1950, a unanimous recommendation was signed by the Special Committee and presented to the President. It recommended that President Truman take the necessary steps to determine the feasibility of a hydrogen bomb. Also, the committee recommended a complete re¬examination of our foreign policy objectives, both diplomatic and military. This advice was followed by Truman. His public statement that day signifies the compromise that was a result of the process of decision making. (see Appendix A)

The recommendation was not without conflict among the three men on the NSC Special Committee. Secretary Johnson was against re-examination of diplomatic and military objectives because of the potential cost of such inquiry. On the other hand, it is probable that Acheson conceded the development of a hydrogen bomb in order to achieve re-examination of policy objectives. The primary role that his department would, and did, play in this re-evaluation is one possible explanation. (Stein, p. 37) Lilienthal was opposed to the compromise because he felt the U.S. was missing perhaps the only opportunity to re¬examine foreign policy objectives before we engage in a massive arms race. (Journals of David Lilienthal, p. 629) Nonetheless the recommendation was made to and accepted by President Truman. Why, given the ever-present debate and conflict, was this done?

Political pressures and consideration were the deciding factor in the decision. Secretary of State Acheson presented a politically sound compromise, and the President followed it. Indeed, the compromise between the three members of the NSC Special Committee shows the nature of compromise in the political field. President Truman was forced, by domestic political pressures, to make a decision on a complex issue. Truman later reiterated this when he stated that, “Occasionally some newspaperman gets wind of the existence of certain military plans and reports them as the fixed position of the government…such reports are often as damaging as they are inaccurate.” (Truman, Memoirs, p. 305.) Senator Johnson’s leak to the press certainly fits this description. Truman faced pressure from the anti-communist public to respond to the newly gained atomic capabilities of the Soviets. Also, China had just fallen to communism. Congressional pressure, from Senators McMahon and Johnson, in turn created increased public pressure. Public discussion of the hydrogen bomb, due mostly to Senator Johnson’s leak, increased and placed greater pressure on Truman. Factored together, it could be argued that these domestic political pressures dictated Truman’s decision in 1950.

These speculations are not without support. The decision to go ahead with the hydrogen bomb was made despite widespread disapproval from leading nuclear scientists. The GAC’s recommendation against implementation is sufficient evidence. The decision to go ahead with the superbomb was made during a time of technological uncertainty. Upon hearing President Truman’s January 31 announcement, GAC member Isador I. Rabi remarked “…here is a statement from the President to do something that nobody knows how to do.” (Stein, p. 18)

During the final NSC Special Committee meeting, Lilienthal was expressing his opinion that a complete re-examination of policy was needed before beginning feasibility studies when President Truman interrupted and said, “…we all could have had all this re-examination quietly if Senator Ed Johnson hadn’t made that unfortunate remark about the super bomb.” He went on to say that, due to the public discussion and excitement that this created, he had no choice but to go on. (Journals of David Lilienthal, p. 632) This is perhaps the most striking evidence that Truman’s decision was dictated by domestic political considerations.

This analysis illustrates the complexity of foreign policy decision making. The implications of the decision to go ahead with the hydrgen bomb are many. The re-evaluation of foreign policy objectivies resulted in NSC-68. In this study, nuclear weapons were deemed as vital to our national defense. This implementation is a large factor in the massive nuclear arms race that accompanied the Cold War. Was Lilienthal’s fear that re-assessment of policy during hydrogen bomb studies would slant the resulting foreign policy recommendation fulfilled? The results (e.g. massive arms race) are fairly conclusive evidence that his fear was realized.

Another result was the increased dependency on force based diplomacy. The spiraling of Cold War tensions beginning in 1950 is a good example of this. Our foreign policy objectives became pre-occupied with the fear of the Soviet Union. The decision to develop a hydrogen bomb may have marked the beginning of the arms race, and subsequently the beginning of many of the problems discussed in the essay.

Did Truman have a sound alternative? Given the amount of domestic and congressional pressure, it is understandable why he thought he had no choice. To delay development of the hydrogen bomb would have been to risk that the Soviets develop one first. This would have been politically disastrous for the Truman Administration. Fear of communism among the American people was high in 1950. Nuclear superiority went a long way in subduing this public fear. Whether or not this superiority provided real security was not of primary concern. Truman was caught between a hesitant group of advisors and an anxious, anti-communistic public and media. Upon review of all factors and variables, Truman opted to begin work toward a hydrogen bomb.

November 1, 1952 the first hydrogen bomb was exploded. “…Our whole purpose was peace; that we didn’t believe we would ever use them (nuclear weapons) but we had to go on and make them because of the way the Russians were behaving.” -Harry Truman (Stein, p. 36)

APPENDIX A

President Truman’s Public Address

January 31, 1950

“It is part of my responsibility as Commander-in-Chief of armed forces to see to it that our country is able to defend itself against any possible aggressor. Accordingly, I have directed the Atomic Energy Commission to continue its hydrogen or super-bomb. Like all other work in the field of atomic weapons, it is being and will be carried forward on a basis consistent with the overall objectives of our program for peace and security. This we shall continue to do until a satisfactory plan for international control of atomic energy is achieved. We shall continue to examine all those factors that affect our program for peace and this country’s security.”

Appendix B

Works Cited

Acheson, Dean. Power and Diplomacy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Acheson, Dean. Present At The Creation: My Years In The State Department. New York: W.W. Norton 6k Company Inc., 1969.

Bernstein, Barton J.. Politics and Policies of the Truman Administration. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970.

George, Alexander. Presidential Decisionmaking in Foreign Policy: The Effective Use of Information and Advice. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1980.

Kennan, George F.. The Nuclear Delusion: Soviet-American Relations In The Atomic Age. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

LaFeber, William. The American Age: United States Foreighn Policy at Home and Abroad Since 1750. New York: W.W. Norton 6k Company, Inc. 1989.

Nathan, James A. and James K. Oliver. United States Foreign Policy and World Order. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresman and Company, 1989.

Public Papers of the Presidents of The United States: Harry S. Truman, 1950. United States Government Printing Office Washington D.C.: Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration, 1965.

Stein, Jonathan B.. From H-Bombs to Star Wars: The Politics of Strategic Decision Making. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books, 1984.

Truman, Harry S.. Memoirs: Volume Two, Years of Hope and Trial. Garden City, New York: Doubleday 6k Company, Inc., 1956.